Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet was born in 1694 in Paris his father was a lawyer and his mother was from minor nobility. He was educated by the Jesuits and wished to become a writer until his father sent him to study law. His father would find him an opportunity to be secretary to the French Ambassador in the Netherlands. When he fell in love with a Protestant refugee he was forced to leave and return to Paris. Here he wrote a series of pamphlets one of which accusing the Regent of incest with his own daughter saw Arouet being placed in the Bastille.

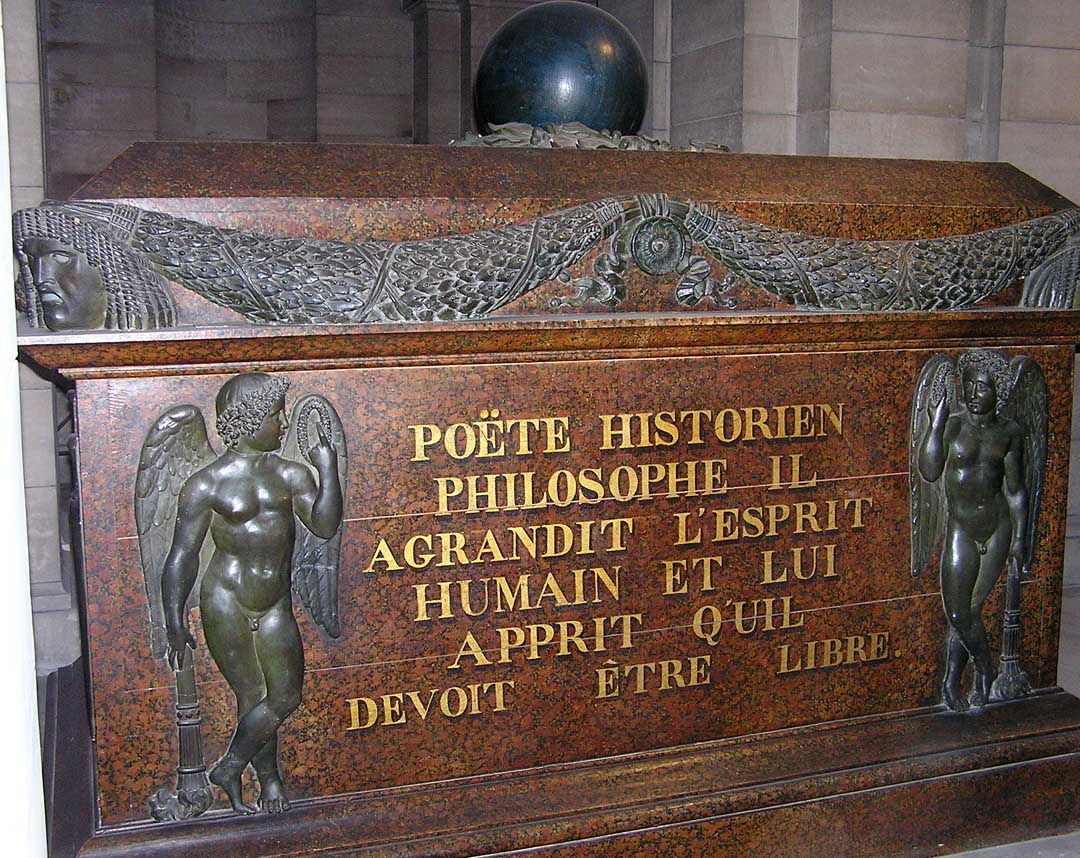

Voltaire’s Tomb in the Pantheon in Paris

Arouet would adopt the name Voltaire as an anagram of the latinised form of his name. He entered into a quarrel with a nobleman in 1726 and challenged the aristocrat to a duel. The nobleman’s family requested a royal letter de cachet to have him imprisoned in the Bastille again with no opportunity to defend himself. Voltaire requested that he be exiled to Britain instead of serving the sentence. The episode could go some way to explain his lifelong thirst for judicial change. Whilst he was in Britain he would be able to compare the French system of absolute monarchy versus the Constitutional monarchy of Albion. When he returned to France after three years he was forced to leave Paris for Lorraine when he published Letters on the English Nation which angered the establishment. He was only formally allowed to re-enter Paris in 1778 only to die shortly afterwards.

During his lifetime Voltaire wrote a series of poetry, plays, historical works and philosophical works. His historical works such as Essay upon the Civil Wars in France and The Age of Louis XIV stressed the importance of social and economic factors in shaping the world rather than simply battles and the work of great men. Both in his written work and in his life he would defend those accused by the church and criticise the clergy for its intolerance. He was a deist who would not conform to traditional religion as he stated in A Treatise on Toleration in 1763 that all men were equal as they had all been created by god. In 1791 the National Assembly would have his remains exhumed and placed in the Pantheon in a ceremony which saw apparently a million people crowd the streets to remember the man and his works.

Tom Paine on Voltaire. Taken from The Rights of Man, Penguin, London (1983) p115

Voltaire, who was both the flatterer and satirist of despotism, took another line. His forte lay in exposing and ridiculing the superstitions which priestcraft united with statecraft had interwoven with governments. It was not from the purity of his principles, or his love of mankind, (for satire and philanthropy are not naturally concordant), but from his strong capacity of seeing folly in its true shape, and his irresistible propensity to expose it, that he made those attacks. They were however as formidable as if the motives had been virtuous; and he merits the thanks, rather than the esteem of mankind.