Storming of the Bastille

With the King’s authority slowly unravelling he decided to encircle the capital with troops. The apparent plan was to defuse the revolutionary elements that were becoming increasingly established in Paris.

Events escalated when the King dismissed the financial controller Necker on the 11th July. Camille Desmoulins in his first significant action of the Revolution jumped on a table with a pistol in hand in the gardens of the Palais Royal and called for action. The crowd attacked the Hôtel des Invalides seizing muskets and then moved to the Bastille to confiscate the gunpowder there.

The Bastille was notorious in French society and believed to be home to many prisoners of the King. By this stage however there were only seven prisoners two of whom were insane. The Marquis de Sade had been a resident but had been moved out ten days previously. The meagre garrison was overseen by the governor Bernard-René de Launay.

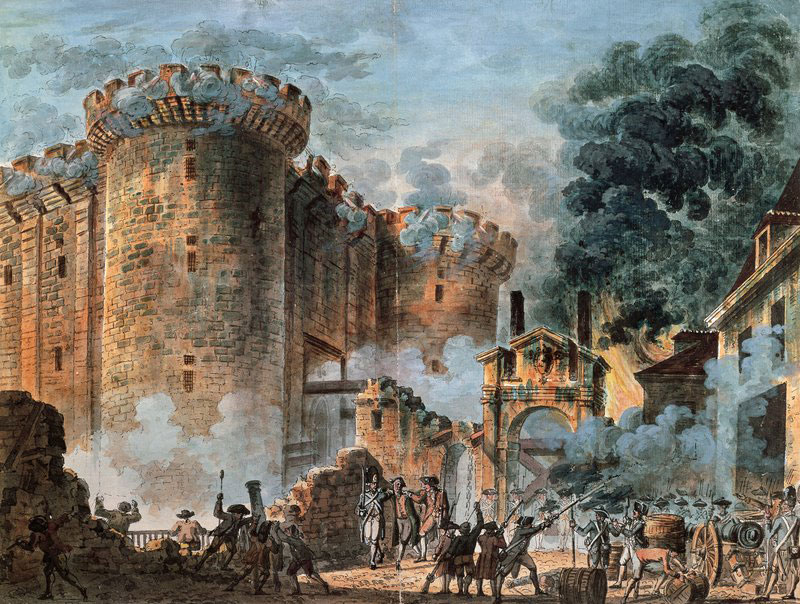

The Storming of the Bastille (Prise de la Bastille) by Jean Pierre Louis Laurent Houёl 1789 in the British Library

Representatives of the crowd called for the surrender of the fortress. Admitted to the fortress the negotiations dragged and the crowd became increasingly aggravated. They surged into the courtyard of the prison. In the chaos that ensued shots were fired. Some sensed that they had been lured into the courtyard by the Governor. As the crowd had begun to bring canons Launay decided to surrender. During the battle ninety eight attackers and one defender died. De Launay was dragged from the building and demanded to be killed rather than face indignity he aimed a kick at a pastry chef. He was killed on the spot and was beheaded with a pen knife. His head was placed on a pike and paraded through the streets. Five other officers were killed.

When the King heard of the attack he was heard to ask, “Is it a revolt?” only to be told, “No sire, it’s not a revolt; it’s a revolution.” The King responded to the crisis by dispersing the troops around the capital. He also recalled Necker and went to Paris himself and accepted the tricolour cockade.

The decision was made to destroy the Bastille. Pierre-François Palloy was given permission to demolish the building. He would then use the resulting rubble to make models of the former prison.

Chateaubriand on the fall of the Bastille. Taken from Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb, François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand, Penguin Classics, London (2014) p102

On 14 July came the fall of the Bastille. I was present, as a spectator, at this attack on a few pensioners and a timid governor: if the gates had been kept closed, the mob could never have entered the fortress. I saw two or three cannon shots fired, not by the pensioners, but by French Guards who had already climbed up to the towers. The Governor, De Launay, was torn from his hiding place, and after undergoing a thousand outrages, was killed on the steps of the Hotel de Ville; Flesselles, the provost of the merchants of Paris, had his brains blown out: this was the sight which heartless optimists thought so fine. In the midst of these murders, the mob indulged in wild orgies, as in the troubles in Rome under Otho and Vitelius. The “victors of the Bastille”, happy drunkards declared conquerors by their boon companions, were driven through the streets in hackney carriages; prostitutes and sans culottes, who were at the beginning of their reign, acted as their escort. The passers-by took off their hats, with a respect born of fear, before these heroes, some of whom died of fatigue in the midst of their triumph.

Jean Paul Marat explains his role in the storming of the Bastille in his publication Friend of the People. Taken from Jean Paul Marat: The People’s Friend by Ernest Belfort Bax, Grant Richards, London (1901) p91-92

At nightfall on the 14th of July, I circumvented the project of surprising Paris by introducing into the city by a ruse several regiments of dragoons and of German cavalry, of which a large detachment had been already received with acclamation. It had just reconnoitred the quartier St. Honore and was about to reconnoitre the quartier St. Germain, when I encountered it on the Pont Neuf, where it was halting to allow the officer in charge to harangue the multitude. The orator's tone appeared to me suspicious. He announced as a piece of good news the speedy arrival of all the dragoons, all the hussars, and the royal German cavalry, who were about to unite themselves with the citizens in order to fight by their side. Such an obvious trap was not calculated to succeed. Although the speaker obtained for himself the applause of a large crowd in all the quarters where he had announced his information, I did not hesitate for an instant to regard him as a traitor. I sprang from the pavement and dashed through the crowd up to the horses' heads. I stopped his triumphal progress by summoning him to dismount his troop and to surrender their arms, to be received again later on at the country's hands. His silence left no doubt in my mind. I pressed the commandant of the city guard, who was conducting these horsemen, to assure himself of them. He called me a visionary; I called him a fool, and seeing no other means of circumventing their project, I denounced them to the public as traitors who had come to strangle us in the night. The alarm I caused by my lusty cries had its effect on the commandant, and my threatening him with denunciation decided him. He made the horsemen turn back and took them to the municipality, where they were requested to lay down their arms. On their refusing, they were sent back to their camp with a strong escort.

It appears that two English servants had taken part in the storming of the Bastille. This report is believed to have come from the British Embassy. Taken from Witnesses to the Revolution American and British Commentators in France 1788-1794, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London (1989) p63

The Marquis de Launey contrary to all precedent fired upon the people and killed several: this proceeding so enraged the populace that they rushed to the very gates with a determination to force their way through if possible: upon this the governor agreed to let in a certain number of them on condition that they should not commit any violence: these terms being acceded to, a detachment of about 40 in number advanced and were admitted, but the drawbridge was immediately drawn up again and the whole party instantly massacred: this breach of honour aggravated by so glaring an act of inhumanity excited a spirit of revenge and tumult such as might naturally be expected.

Letter IV from the summer of 1790 Helen Maria Williams recounts her journey to the site of the Bastille. Taken from Letters Written in France, Broadview Literary Texts, Ormskirk (2002) p73-74

Before I suffered my friends at Paris to conduct me through the usual routine of convents, churches and palaces, I requested to visit the Bastille; feeling a much stronger desire to contemplate the ruins of that building than the most perfect edifices of Paris. When we got into the carriage, our French servant called to the coachman, with an air of triumph, “A la Bastille- mais nous n’y resterons pas.” (To the Bastille, - but we shall not remain there.) We drove under that porch which so many wretches have entered never to repass, and alighting from the carriage descended with difficulty into the dungeons, which were too low to admit of our standing upright, and so dark that we were obliged at noon-day to visit them with the light of a candle. We saw the hooks of those chains by which the prisoners were fastened round the neck, to the walls of their cells; many of which being below the level of the water, are in a constant state of humidity; and a noxious vapour issued from them, which more than once extinguished the candle, and was so insufferable that it required a strong spirit of curiosity to tempt one to enter. Good god! And to those regions of horrors were human creatures dragged at the caprice of despotic power…….

There appears to be a greater number of these dungeons than one could have imagined the heard heart of tyranny itself would contrive; for, since the destruction of the building, many subterraneous cells have been discovered underneath piece of ground which was enclosed within the walls of the Bastille, but which seemed a bank of solid earth before the horrid secrets of this prison house were disclosed. Some skeletons were found in these recesses, with irons still fastened on their decaying bones.

After having visited the Bastille, we may indeed be surprised, that a nation so enlightened as the French, submitted so long to the oppressions of their government; but we must cease to wonder that their indignant spirits at length shook off the galling yoke.

Barère on William Pitt and the British government’s reaction to the storming of the Bastille in 1789. Taken from Memoirs of Bertrand Barère Volume 1, H. S. Nichols, London (1896) p221-222

When the French Revolution broke out on the i4th .of July, 1789, it was the object of Europe's admiration and England's dismay. The enemy and rival of France, England only busied herself henceforth in attempts to hinder the progress of French liberty; she was eager to revenge herself on the Bourbons, who had favoured the independence of the United States of America, and she resented the great influence France would possess when armed with all the rights and means which liberty would give to a warlike, intelligent and enlightened nation. At this period the Prime Minister, a Tory, a headstrong and semi -lunatic person, ruled England one William Pitt son of the famous Earl Chatham, who, in imitation of Hasdrubal, caused his son to swear eternal enmity to the French nation. Pitt dispatched diplomatic emissaries to frighten all the foreign cabinets at the great rebellion of the French. What was to become of the divine right of kings on the continent if this mania for reform was not arrested and condemned on principle ? Plots were started by intriguing agents from England, and were for some time overlooked, until the time came when the Committee of Investigation nominated by the National Assembly discovered the cause of the disturbances in Paris and of the riots which disturbed the provinces.

The Cabinet of St. James' carried its plans of counter-revolution against this mainspring of liberty still further, and assembled a congress at Pillnitz, supported by the Bourbon princes who had emigrated from France. It was there that the partition of France was decided on, in imitation of the partition of Poland. To deprive a people of its nationality and of its territory was the radical policy of Pitt, the English minister, who found his model in the action of the three northern powers who partitioned Poland to prevent it being a nation or its people free. All these preparations for internal riots and for foreign wars were accomplished and subsidised in 1791, a period when the national constitution was just about to get to work.

This congress at Pillnitz, followed by the conference and treaty of Pavia, was the basis of all the coalitions of the kings of Europe against France and its liberty. It was a reaction which underwent changes of form and of leaders, but was constantly in opposition to France and her liberties. These cost the Cabinet of St. James' twenty-one milliards of francs, which formed its national debt from 1791 to 1815.